Imagine paying $5 for a loaf of bread, $10 for a litre of milk, or $150 for a tank of petrol. Inflation is hurting Australians and hat’s what some face as inflation hit its highest level in more than three decades.

Inflation is the general increase in the prices of goods and services over time. It reduces the purchasing power of money and erodes the value of savings and investments.

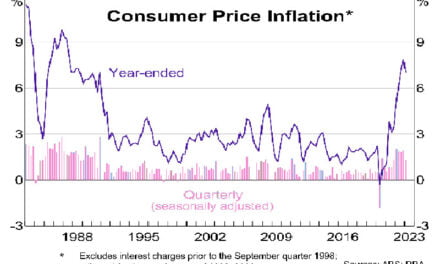

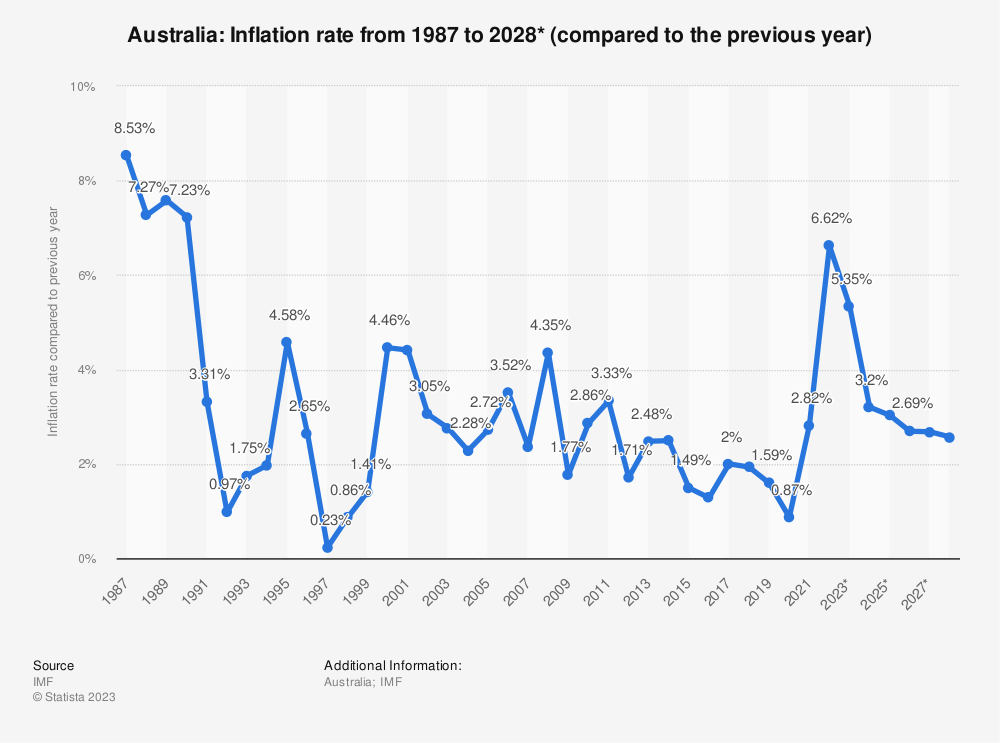

Australia’s inflation rate has soared to 7 percent in the year to March, down from 7.8 percent in December, but still more than twice the top of the Reserve Bank’s target range of 2-3 percent.

Inflation Is Hurting Australians

This means the average cost of living has increased by 7 percent in the past year, while wages only increased by 2.1 percent.

Some prices rose even faster than the average, such as medical services (+4.2 percent), tertiary education (+9.7 percent), gas and other household fuels (+14.3 percent), fruit and vegetables (+2.4 percent), and snacks and confectionary (+4.1 percent).

RBA says the main drivers of inflation are the global supply chain disruptions caused by the government’s COVID-19 response, the surging demand for goods and services as economies reopen, the rising energy and commodity prices, and government fiscal and monetary stimulus measures that boosted household incomes and spending.

The high inflation has hurt many Australians, especially those on low and fixed incomes, such as pensioners, students, and welfare recipients.

Many people are now unable to afford essentials, such as food, rent, utilities, and transport.

It has also increased the cost of borrowing and servicing debt, such as mortgages, car loans, and credit cards.

inflation rate in australia. Chart by Statista.

What The RBA Is Doing

The high inflation has also put pressure on the Reserve Bank. The RBA responded by raising interest rates sooner and faster than expected, nullifying their previous statements.

The Reserve Bank is responsible for maintaining price stability and supporting economic growth and employment.

It does this by setting the cash rate, which is the interest rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans.

The cash rate influences other interest rates in the economy, such as mortgage rates, deposit rates, and business loan rates.

The Reserve Bank uses the cash rate to control inflation by making borrowing more or less expensive.

When inflation is too high, the Reserve Bank raises the cash rate to slow down spending and demand.

When inflation is too low, the Reserve Bank lowers the cash rate to stimulate spending and demand.

What The RBA Did

The Reserve Bank kept the cash rate at a record low of 0.1 percent since November 2020 to support the economic recovery from the pandemic.

The Reserve Bank had previously announced it would start raising the cash rate from late 2023 or early 2024.

In response to the rising inflation and strong economic growth, RBA started raising rates.

In November 2020, the Reserve Bank Board introduced a bond purchase program. The aim was to support job creation and the recovery of the Australian economy from government policy around the COVID-19 actions. They purchased $281 billion of Australian, state and territory government bonds between November 2020 and February 2022. They already realised it is very difficult to measure the effects of their buying program.

RBA also signaled a reduction in its bond-buying program, which is another way of injecting money into the economy and keeping interest rates low.

RBA Expectations

The Reserve Bank expects that these measures will help bring inflation back to its target range over time.

However, it has also warned that raising interest rates too quickly or too high could cause job losses and hurt economic growth.

It has also said that it will not raise interest rates until actual inflation is sustainably within its target range, not just forecast to be so.

It also said it will take into account other factors, such as wages growth, unemployment, household debt, housing affordability, and financial stability.

The Reserve Bank urged Australians to be patient and prepared for higher interest rates in the future.

It has also advised Australians to shop around for better deals on their loans and savings accounts. This may be a distraction from the damage it causes.

Not surprisingly, the RBA is keen to blame this inflation on “the pandemic” and “Ukraine.”

Reserve Bank Governor. youtube screenshot.

The Government’s Latest Budget

The Albanese government’s second budget focuses on providing cost of living relief for households and small businesses amid high inflation and rising interest rates. It includes a $14.6 billion package that aims to lower energy bills, increase income support payments, and boost childcare subsidies. However, some economists warned that the budget is too expansionary and could add to inflationary pressures and force the Reserve Bank to raise rates further. The government rejected those concerns, saying that the budget measures will not worsen inflation and that some will ease price pressures. The government also projected a $4.2 billion surplus for this year, the first in 15 years, thanks to strong mining profits and “a robust job market.”

Key Takeaways:

• Inflation is the general increase in the prices of goods and services over time.

• Australia’s inflation rate soared to 7 percent in the year to March, down from 7.8 percent in December, but still more than twice the top of the RBA target range of 2-3 percent.

• This hurt many Australians, especially those on low and fixed incomes, reducing their purchasing power and increasing their cost of living.

• The high inflation has also put pressure on the Reserve Bank and they raised interest rates sooner than they promised.